The Unrealised Infrastructure of Heritage

Let me start with the obvious. Australia is growing.

More people living in the dense centres of our major cities mean more and new infrastructure will be needed to move them about and to accommodate their working and social lives.

It goes without saying that in terms of sustainability we should keep all we have unless the benefits of change outweigh all the values—cultural, economic and other—they possess. And we should be prudent where limited resources need to be spent.

Growth and development, whether it be new roads or railways or densification of our suburbs, can seem at odds with heritage—or at least its conservation. What is not often recognised is that our heritage places are themselves infrastructure—infrastructure often under-used.

Heritage and infrastructure seem often to concentrate on the mitigation or minimisation of harm to and loss of heritage rather than the re-use and reinforcement of it. The former may be as simple as the diversion of a route or, where loss is unavoidable, strategies of recording and interpretation. Retention and re-use of our heritage infrastructure presents different challenges and opportunities beyond the dug and burnt clay of which they are made.

To understand these challenges and envisage the future of heritage, let’s look at some facts and figures. Our population is growing, bringing with it the challenges of an aging one. In addition to natural increase balanced by births and deaths, almost 200,000 people come here from all over the globe every year. Immigration alone would account for a city the size of Hobart each year or a new Canberra every other year.

To encourage a greater spread of settlement over the world’s third least densely populated country, Australia now has an immigration policy which counts everywhere outside Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane as ‘designated regional areas’—areas that need both to attract skilled workers and to relieve the burden on those three cities.

In the context of demographics that forecast a growing and aging population, economists looking to the medium to long term future say key sectors of development and growth include aged care, agribusiness, education and tourism. There are many cross-overs of issues in these sectors. But let’s focus on what the interface of heritage and one of these might be—aged care.

Challenges for New and Old

Most people would agree that aging in place—remaining in one’s own home as long as possible—is a preferred way of living in the later years of life. It enables older people to remain healthy, active and socially engaged members of their communities. With community care supporting this approach, we need fewer resources to build and maintain new residential aged care—new infrastructure. At the same time, other models are emerging such as congregated housing and intentional communities.

What changes may be necessary? And how might that change be managed in a way that retains and reveals the heritage places, stories, memories and uses that are special? In practical and tangible terms, the built environment and public domain need to be accessible to all users.

Medical advancements notwithstanding, an older population is generally a less physically able one. An accessible environment is not only more equitable for all; it also means greater independence for longer, in ways that benefit both older generations and those around them.

It presents opportunities for continued social engagement outside the home, whether it be shopping locally, catching up with friends, volunteering or the intangible transfer of memory and skills—showing a child how to thread a needle and sew on a button, for instance, or teaching them how to spin an endless yarn.

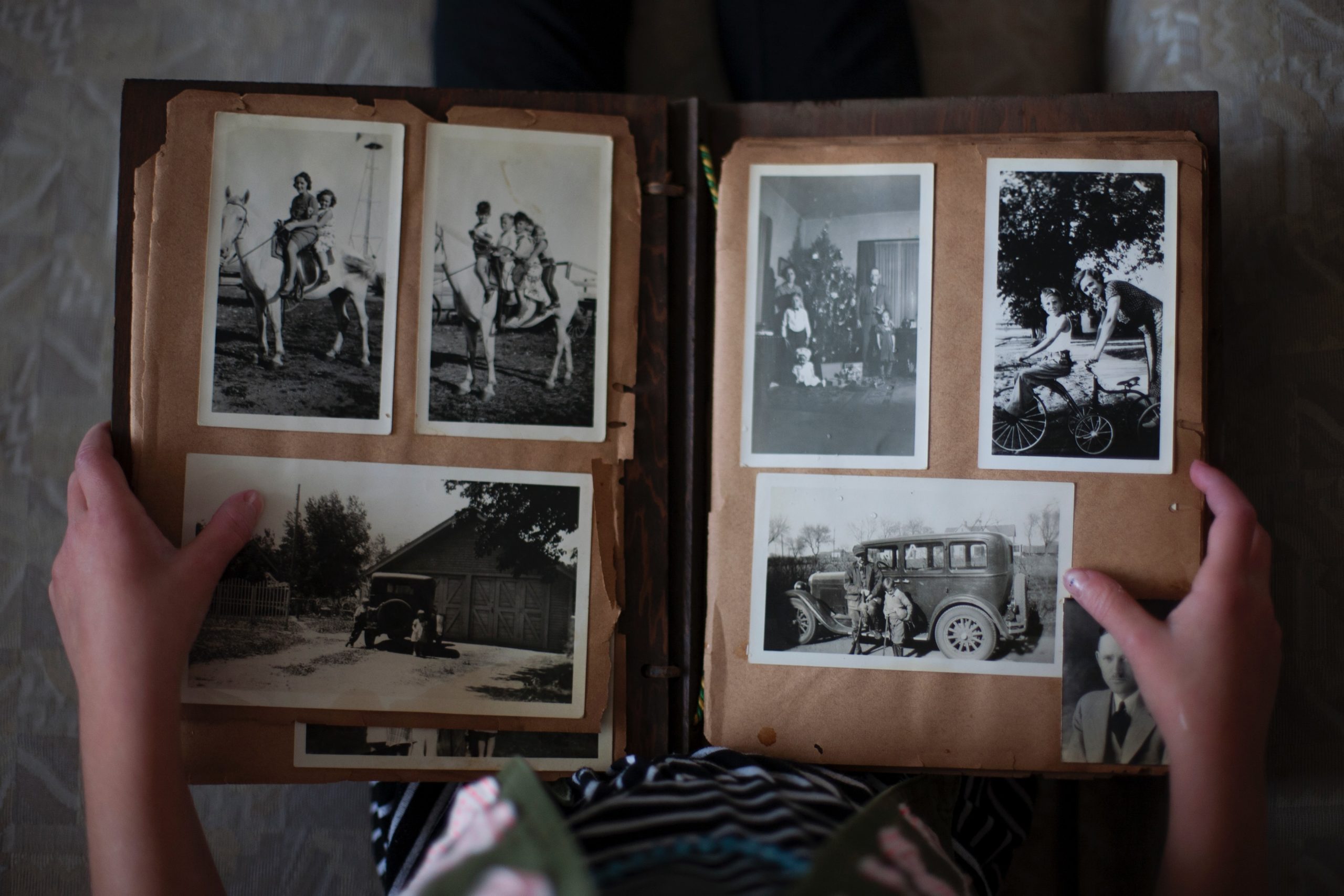

Along with reduced mobility for the aging come diseases affecting memory and cognition. Experts in dementia have found that objects, rather than words and numbers, assist orientation and that familiar settings bring comfort and connection. Trying to negotiate a once-familiar neighbourhood transformed by redevelopment or being unable to connect actual long-term memories with the places those memories were laid down would be unsettling to say the least. Memories of place become more than nice-to-have, sepia-toned nostalgia but part of a person’s wellbeing environment.

An aging population also means more people are needed to care for them. Some will be family—this may mean a move away from the nuclear family and a shift in the type of housing in which we dwell. Some may be friends intentionally congregating in support of one another.

In terms of religious faith, the proportion of Australians with no religion increases and the proportion of Christians continues to decline. At the same time, numbers of Hindus and Muslims continue to rise.

Since the 1970s, we have become used to the conversion of churches to much-loved homes with their lofty, cathedral ceilings well suited to open living and dining areas. The redundancy of church buildings in the 1970s came in part by the Uniting Church of Australia consolidating the congregations of the churches which it united. But how will the potential oversupply of Christian places of worship interact with a growing need for mosques and Hindu temples?

Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia is a long-standing example of the adaptive re-use of a cathedral to a mosque—and one on a monumental scale both physically and in historical significance.

Whereas the results of the conversion of what had been the world’s largest cathedral for more than a thousand years were instant, violent and destructive, adaptive re-use of this ilk—going forward—may be achieved with sensitive dialogue, respect for spiritual and social associations, and the layering and coexistence of values and memories.

Whether born here or moved since birth, whether permanent or transient, we all have a right to appreciate, and where appropriate access, heritage—places, objects, memories and stories.

We also have a right to hear the full story, to be told and be able to listen to hidden heritage—the ongoing connection to Country of the First Australians and the sometimes uncomfortable truths that have led to the Australia of today so we might reconcile the past with the future.

Moreover, we have an obligation as custodians of that which we inherit to conserve it. But we and those to come also have a right to make our own places and memories while not erasing what has gone before or prejudicing what value may come yet. We may not be able to keep all fabric and spaces as they are or once were, but it is our duty to keep and retell memories and stories.

From engaging with communities to identify intangible heritage values to the modification of buildings and public spaces to make them accessible to all, GML plays a role as an identifier and facilitator of heritage and its conservation—and a mediator for coexistence of values.

The future is inevitable—as inevitable as the demographic and macroeconomic challenges and opportunities we face. The future of heritage will be to recognise and work with these forces to identify, conserve, prudently exploit and renew places, objects, memories and stories.

The future of heritage is ours to make, but it cannot be made with anything more than what we have, what we have had and what we can contribute. What we have more of is people, and it is they who will conserve and build upon our shared heritage. The unrealised infrastructure of heritage is people—people working together.