Walking tour—Sydney’s ever changing heritage

To celebrate the ICOMOS General Assembly 2023 coming to Sydney for the first time in September, GML has created a self-guided tour of Sydney's ever changing heritage.

The tour starts at Tumbalong/Cockle Bay, now Darling Harbour, on Gadigal Country. ‘Tumbalong’ means a place where seafood is found. This is reflected in the extensive shell middens found along the harbour’s shorelines.

Colonisation profoundly transformed Darling Harbour and the Gadigal’s resources. The land grants, reclamations, industrialisation, shipping, export, technological change, to today’s revitalised tourism and leisure precinct, are all part of Sydney’s ever changing heritage.

Download the map here. The walking tour should take you 2—2.5hours. Train stations are indicated on the map if you need to get around quickly.

Keep scrolling to read more about the tour stops.

Stop 1: Barangaroo

The headland is named Barangaroo after a courageous Cammeraygal woman who resisted colonists’ entreaties. When her partner, Wangal man Bennelong, attended the Governor’s dinner she refused to join him, and expressed her anger by breaking one of his fishing spears.

During the Great Depression era this foreshore became known as the “Hungry Mile”, because of the hundreds of men who walked between wharves trying to secure a day’s work.

Other chapters in the maritime history of Barangaroo include untold arrivals and departures from this waterfront–of migrants coming to a new land and the tearful farewells for Australian troops during World War II.

The recent development at Barangaroo has opened up this waterfront precinct to the public for the first time in more than 100 years.

‘8.40am: surplus labour’, photo taken by Arthur Aitken, 1927. (Source: Noel Butlin Archives Centre, Australian National University)

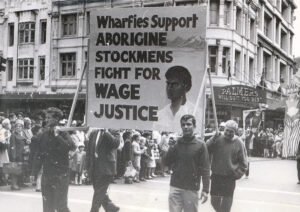

‘Wharfies support Aborigine stockmen’s fight for wage justice’, photographer unknown, 1966. (Source: Noel Butlin Archives Centre, Australian National University)

Stop 2: Walsh Bay Finger Wharves

The Walsh Bay finger wharves were once the site of fast-paced dangerous work unloading cargo. Sydney Harbour Trust’s construction of the wharves from 1906-1920 represented a globally advanced design for a shipping port.

During the 1930s, the unionized maritime workforce, with many Aboriginal workers, was fearless in leading campaigns for wages, equity, education and land rights.

Today, the NSW State Heritage listed wharves have been refurbished and revitalised, and are now home to some of Australia’s leading performing arts companies.

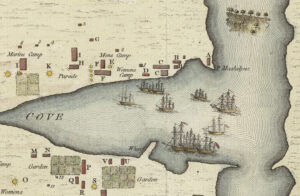

Stop 3: Dawes Point

The area was originally known by the Aboriginal names of Tar-ra and Tullagalla. It became known as Dawes Point, named after William Dawes, an English Lieutenant and the colony’s first astronomer.

Dawes established a rudimentary observatory here in 1788, studying not only the stars but also Sydney’s Aboriginal language with Patyegarang, a young Aboriginal woman. This friendship serves as one of the earliest recorded cultural exchanges between Europeans and Aboriginal people.

The southern pylon of the Sydney Harbour Bridge is located in Dawes Point. Opening in 1932, the Sydney Harbour Bridge was constructed over 8 years and has become one of Australia’s most famous landmarks. An incredible feat of engineering, its construction required c1400 workers, 52,800 tonnes of steel and 6 million rivets.

Sketch & description of the settlement at Sydney Cove Port Jackson, Francis Fowler, 16 April, 1788. (Source: National Library of Australia)

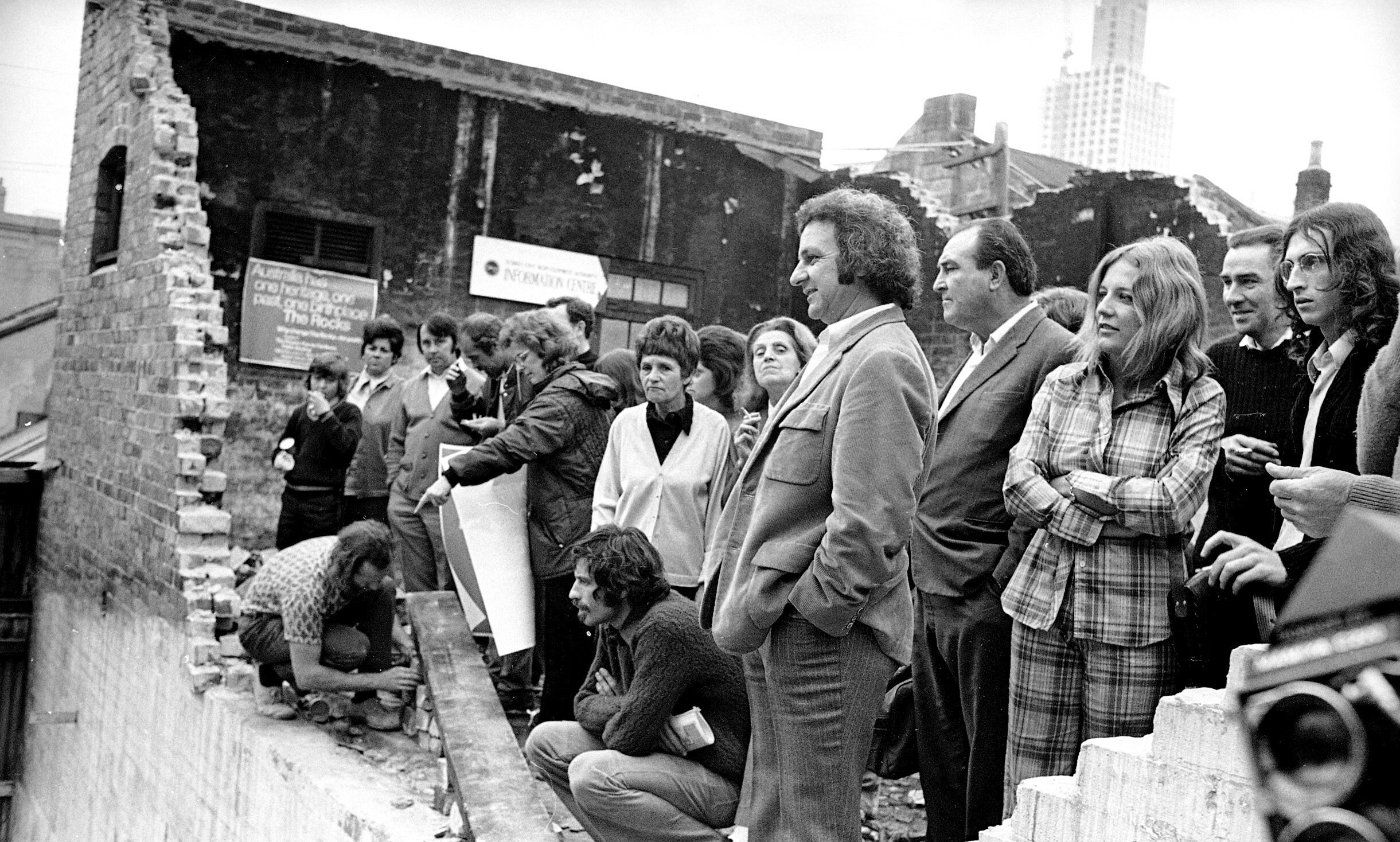

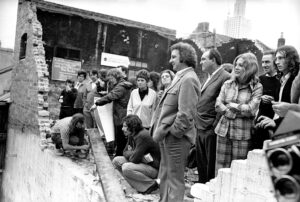

Jack Mundey leads a protest against demolition at The Rocks in Sydney, 1973. (Source: Fairfax Media)

Stop 4: Jack Mundey Place

Sydney was one of the first places in the world to have Green Bans—industrial action that prevented development of significant landscapes and places.

Led by Jack Mundey, the Builders Labourers Federation fought alongside members of the community to save The Rocks from over-development, as well as places such as Centennial Park, Glebe, Kings Cross, and Woolloomooloo.

In recognition of Jack’s involvement in saving The Rocks, a section of Argyle Street was renamed Jack Mundey Place in 2007.

Stop 5: The Big Dig

The Big Dig site, between Cumberland and Gloucester Streets in The Rocks, is an area of land containing archaeological remains from the late 18th century, the time of Australia’s first European settlement.

With the foundations of over 30 homes and shops uncovered and over 750,000 artefacts excavated, it is one of the largest urban archaeological excavations in Australia.

These artefacts are traces of a densely populated maritime village, where Cantonese, Gaelic, Maori and many other languages echoed in the streets.

Excavations at the Big Dig site, 1994. (Source: GML Heritage)

Chinese hawker at Argyle Street, The Rocks by Arthur Syer c1885-1890. (Source: State Library of New South Wales)

Stop 6: Circular Quay

Circular Quay, or Warrane as it was originally known, was an important resource and meeting place for Sydney’s Aboriginal groups.

It was transformed into a maritime industrial site following colonisation. People from many different nations established themselves at the Quay. Chinese traders and businesses were positioned in proximity to the wharves, and street hawkers were regularly seen selling their goods.

Eventually, commercial maritime activity ceased at Circular Quay, and it became a hub for passenger ferries, trains and buses taking residents and tourists to a variety of locations around the harbour.

Stop 7: Bennelong Point

Home to the Sydney Opera House, the youngest building to be inscribed on the World Heritage list. Bennelong Point is a place of many pasts.

Known to the Gadigal people as Tubowgule, Bennelong Point is part of a rich cultural landscape where Aboriginal people have gathered for thousands of years. Tubowgule’s present name honours Woollarawarre Bennelong, a member of the Wangal people at the time of the colonists’ arrival.

In 1790, Governor Phillip constructed a hut on the site for Bennelong, who was an important cross-cultural mediator between the colonist government and local Aboriginal people.

In 1957, an unknown Danish architect, Jørn Utzon, won the international design competition for the Sydney Opera House.

To many, it is a symbol of Australia’s modernity and creativity.

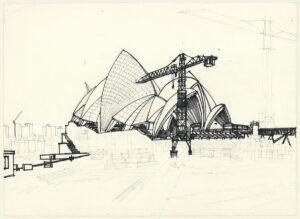

Sydney Opera House under construction, 1969. Drawing by Mervyn Smith. (Source: State Library of South Australia)

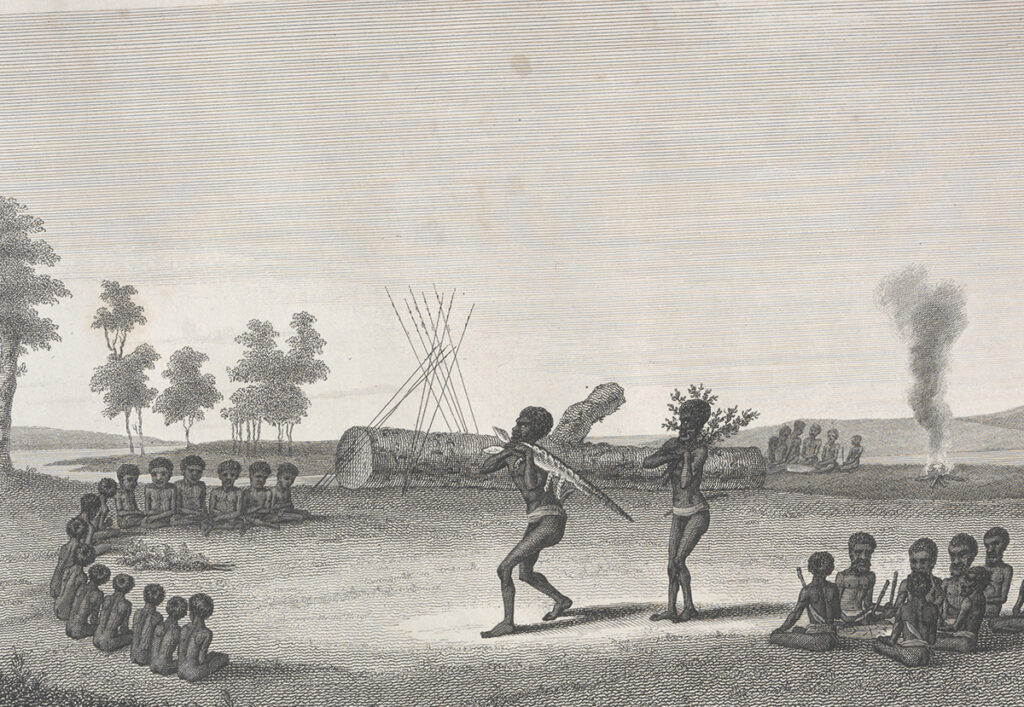

‘Yoo-long Erah-ba-diang 2’ in An account of the English colony in New South Wales by David Collins. (Source: State Library of New South Wales)

Stop 8: Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney

Discover the Botanic Gardens’ Aboriginal heritage and explore the site of the first government farm, that is Australia’s oldest scientific institution for botany and horticulture.

The Gardens have long been associated with traditional gatherings. A Yoolong Erah-ba-diang ceremony for young Aboriginal men was held here and recorded by David Collins in 1795.

Today the Garden stands as a major participant in the worldwide network of botanic gardens, advancing science, conservation research and environmental education.

Stop 9: Museum of Sydney, on the site of First Government House

Here in 1788 on the land of the Gadigal people, Governor Arthur Phillip built Government House. In this house and its later additions, the first nine governors of NSW lived and worked.

It was on this same site that Aboriginal men Bennelong and Colbee were incarcerated in November 1789, in an attempt to learn Aboriginal language, customs and knowledge of the country. Colbee fled after two and a half weeks but Bennelong did not escape for five months.

These early contact stories and the continuing story of Sydney’s Aboriginal people are told at the Museum of Sydney which now occupies the site.

First Government House, Sydney c1807, by John Eyre. (Source: State Library of New South Wales)

‘Hiring Immigrants at the Depot, Hyde Park’, Australian Town and Country Journal, 19 July 1879. (Source: State Library of New South Wales)

Stop 10: Hyde Park Barracks

Opening in 1819, the World Heritage inscribed Hyde Park Barracks is a convict designed and built barracks that is part of the Australian convict serial listing.

The Barracks also served as a women’s immigration depot and asylum, and later law courts and government offices.

It’s now an immersive museum that tells the stories of the thousands of men, women and children held or housed there, and the Aboriginal communities profoundly impacted by the relentless push of colonial expansion.